Iraq's prohibition zeal threatens Baghdad's boozy subculture

The smell of dampness rises through the dust at a private club in central Baghdad, one of many shut in a crackdown on alcohol sales in Iraq.

"We appealed to all authorities in the country, but no one listened to us," said the owner, a Christian who asked not to be named.

Although a law banning the sale and import of alcohol was passed in 2016 and came into force at the start of last year, its enforcement had been patchy.

But conservative lawmakers have a majority in parliament, and have pushed for stronger action.

Several private "social" clubs that have operated in Baghdad for decades were sent official letters in November forbidding them from manufacturing and serving alcoholic beverages.

In the case of violations, "legal action will be taken," the letters said.

Dozens of establishments have closed in recent months and their owners, often from the Yazidi community, regularly demonstrate in the centre of Baghdad.

The law has proved hugely unpopular with Christians and Yazidis, but many Muslims also drink.

The Christian club owner said his premises held bingo tournaments and music evenings, and "didn't bother anyone" in the neighbourhood.

But customers have deserted the club and the owner has just one employee left to guard the building, now shrouded in dust with playing cards and dirty glasses strewn around the main room.

- 'Cat and mouse' -

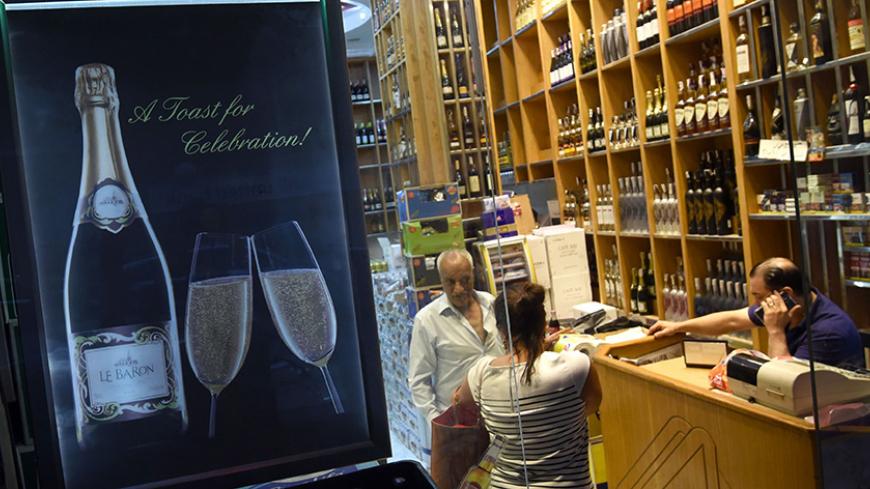

However, Iraqis are still free to grab a drink in the autonomous Kurdistan region, or a bottle in the duty-free shops at Baghdad International Airport.

Delivery services and even a few shops in the capital still supply booze.

"We are playing a game of cat and mouse with the authorities," said a shopkeeper from behind the small window of a premises that looked closed from the outside.

To keep their business running, one of the employees acts as a lookout, closing the window each time a security patrol passes.

"Society is hypocritical, because civil servants close our shops and then come to buy alcohol in civilian clothes," he said.

A manager at a nearby social club said it had more than 50,000 members, largely because of its bar.

"We no longer have customers," he said from his office overlooking the club's empty restaurants.

The Interior Ministry did not respond to AFP's request for comment.

Ministry spokesman General Miqdad Miri said in September that some "bars and gambling halls" were being shut because they were "hotbeds of crime" with "gangs, criminals, organ traffickers and murderers".

- Prohibition ineffective -

It is not just the government that objects to alcohol.

Armed groups have attacked and blown up liquor shops in recent years.

Razaw Salihy, Amnesty International's Iraq researcher, said prohibition policies had proven ineffective and "instead often fuel violence, illicit markets, and human rights violations".

And the outright ban seems to be inconsistent with other rules -- like a February 2023 decision to impose a 200 percent customs tax on "imported alcoholic beverages".

Yazidi lawmaker Mahma Khalil joined merchants in filing a legal complaint arguing the law was unconstitutional, but the court rejected their request.

He said the law had affected between 150,000 and 200,000 workers in sectors linked to the sale of alcohol.

Several million dollars were being lost every month, he said.

Yazidi and Christian entrepreneurs, some who have been in Baghdad since the 1960s, were now thinking of moving overseas or heading for the Kurdish region, he said.

"As Yazidis, just like Christians, we have the constitutional right... to practice our customs, to sell, import and consume alcoholic beverages," he said.