4,000-year-old town discovered hidden in Arabian oasis

The discovery of a 4,000-year-old fortified town hidden in an oasis in modern-day Saudi Arabia reveals how life at the time was slowly changing from a nomadic to an urban existence, archaeologists said on Wednesday.

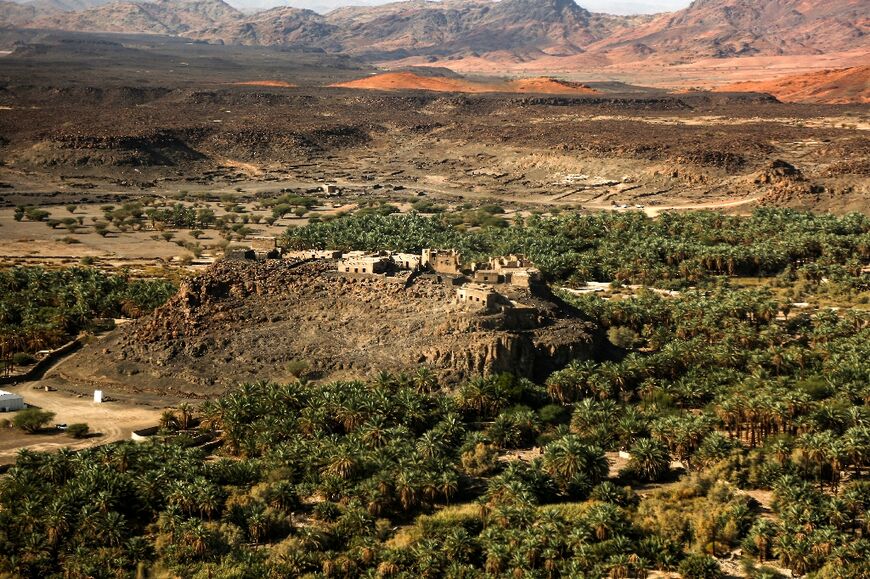

The remains of the town, dubbed al-Natah, were long concealed by the walled oasis of Khaybar, a green and fertile speck surrounded by desert in the northwest of the Arabian Peninsula.

Then an ancient 14.5 kilometre-long wall was discovered at the site, according to research led by French archaeologist Guillaume Charloux published earlier this year.

For a new study published in the journal PLOS One, a French-Saudi team of researchers have provided "proof that these ramparts are organised around a habitat", Charloux told AFP.

The large town, which was home to up to 500 residents, was built around 2,400 BC during the early Bronze Age, the researchers said.

It was abandoned around a thousand years later. "No one knows why," Charloux said.

When al-Natah was built, cities were flourishing in the Levant region along the Mediterranean Sea from present-day Syria to Jordan.

Northwest Arabia at the time was thought to have been barren desert, crossed by pastoral nomads and dotted with burial sites.

That was until 15 years ago, when archaeologists discovered ramparts dating back to the Bronze Age in the oasis of Tayma, to Khaybar's north.

This "first essential discovery" led scientists to look closer at these oases, Charloux said.

- 'Slow urbanism' -

Black volcanic rocks called basalt concealed the walls of al-Natah so well that it "protected the site from illegal excavations", Charloux said.

But observing the site from above revealed potential paths and the foundations of houses, suggesting where the archaeologists needed to dig.

They discovered foundations "strong enough to easily support at least one- or two-storey" homes, Charloux said, emphasising that there was much more work to be done to understand the site.

But their preliminary findings paint a picture of a 2.6-hectare town with around 50 houses perched on a hill, equipped with a wall of its own.

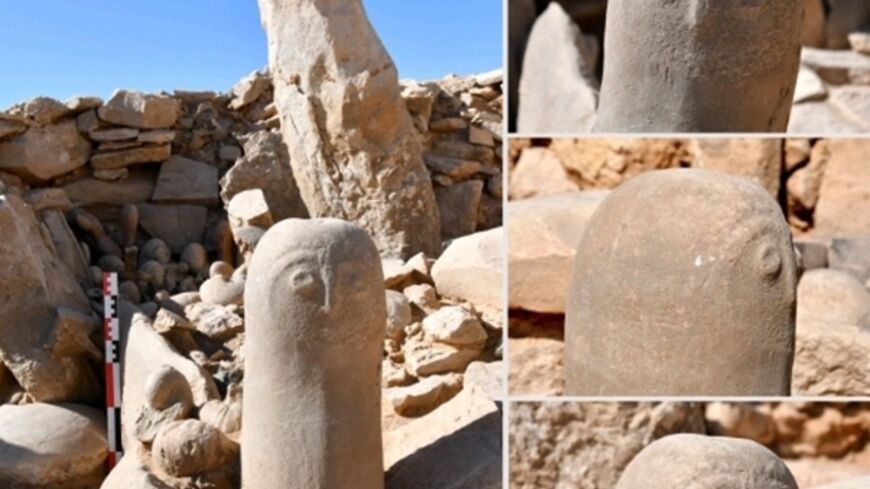

Tombs inside a necropolis there contained metal weapons like axes and daggers as well as stones such as agate, indicating a relatively advanced society for so long ago.

Pieces of pottery "suggest a relatively egalitarian society", the study said. They are "very pretty but very simple ceramics", added Charloux.

The size of the ramparts -- which could reach around five metres (16 feet) high -- suggests that al-Natah was the seat of some kind of powerful local authority.

These discoveries reveal a process of "slow urbanism" during the transition between nomadic and more settled village life, the study said.

For example, fortified oases could have been in contact with each other in an area still largely populated by pastoral nomadic groups. Such exchanges could have even laid the foundations for the "incense route" which saw spices, frankincense and myrrh traded from southern Arabia to the Mediterranean.

Al-Natah was still small compared to cities in Mesopotamia or Egypt during the period.

But in these vast expanses of desert, it appears there was "another path towards urbanisation" than such city-states, one "more modest, much slower, and quite specific to the northwest of Arabia", Charloux said.