More than 230 mn female genital mutilation survivors worldwide: UNICEF

The number of female genital mutilation survivors tops 230 million worldwide, UNICEF said in a new report Thursday, an increase of 15 percent since 2016 despite progress against the practice in some countries.

"It is indeed bad news. This is a huge number, a number that is bigger than ever before," said Claudia Coppa, lead author of the report released to coincide with International Women's Day.

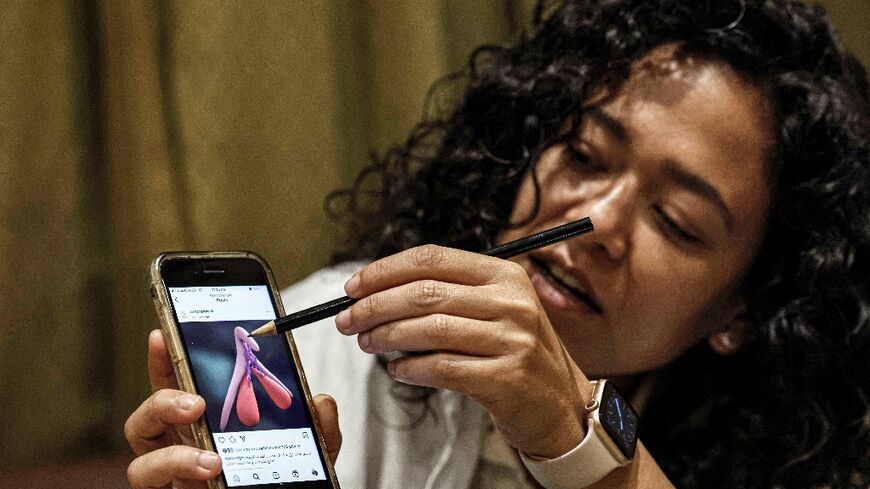

Female genital mutilation, known as FGM, can include partial or total removal of the clitoris as well as the labia minora, and suturing of the vaginal opening to narrow it.

FGM, which can cause fatal bleeding or infections, can also have long-term consequences such as fertility problems, childbirth complications, stillbirth and painful sexual intercourse.

Africa is home to the most number of FGM survivors with more than 144 million, ahead of Asia (80 million) and the Middle East (six million), according to the survey of 31 countries where the practice is common.

The overall increase is largely due to population growth in certain countries but the report highlighted progress in reducing its prevalence in other places.

In Sierra Leone, the percentage of girls aged 15 to 19 who have undergone genital mutilation has fallen in 30 years from 95 percent to 61 percent.

Ethiopia, Burkina Faso and Kenya also recorded strong declines.

But in Somalia, 99 percent of women between 15 and 49 have undergone genital mutilation, as well as 95 percent in Guinea, 90 percent in Djibouti and 89 percent in Mali.

"We're also seeing a worrying trend that more girls are subjected to the practice at younger ages, many before their fifth birthday," UNICEF chief Catherine Russell said in a statement.

"That further reduces the window to intervene. We need to strengthen the efforts of ending this harmful practice."

- 'Remember the pain' -

Progress needs to increase to 27 times the current level to eradicate the practice by 2030, as called for in the UN's Agenda for Sustainable Development.

But even if perceptions are evolving, FGM "has been in existence for centuries. So changing social norms and practices that are related to this norm takes time," Coppa said.

"In some societies, for example, it is considered a necessary rite of passage, in other contexts it is a way of preserving, for example, the chastity of girls. It's a way of controlling girls' sexuality," she said.

Mothers may personally oppose the procedure and "remember the pain... but sometimes the pain is less than the shame, is less than the consequences that they will have to witness, them and their daughters, if they do not conform to expectations."

"These are not cruel mothers," Coppa said. "They're trying to do what they think is expected of them and their daughters."

Girls who have not undergone FGM, for example, might face "repercussions" such as not being considered for marriage.

UNICEF, the UN children's agency, continues to push for laws prohibiting FGM, but also the importance of girls' education in its eradication.

As for the role of men and boys, while in some countries they favor the continuation of FGM, in others women and girls are the ones reluctant to abandon the age-old practice.

But the men and boys "remain silent.... And this silence gives the impression that there is active acceptance of the practice. So everybody needs to take a stand," Coppa said.