In Iran, Bahai minority faces persecution even after death

A flattened patch of earth is all that remains of where the graves once stood –- evidence, Iran's Bahais say, that their community is subjected to persecution even in death.

Beneath the ground in the Khavaran cemetery in the southeastern outskirts of Tehran lie the remains of at least 30 and potentially up to 45 recently-deceased Bahais, according to the Bahai International Community (BIC).

But their resting places are no longer marked by headstones, plaques and flowers, as they once were, because, said the BIC, this month Iranian authorities destroyed them and then levelled the site with a bulldozer.

The desecration of the graves represents a new attack against Iran's biggest non-Muslim religious minority which has, according to its representatives, been subjected to systematic persecution and discrimination since the foundation of the Islamic republic in 1979.

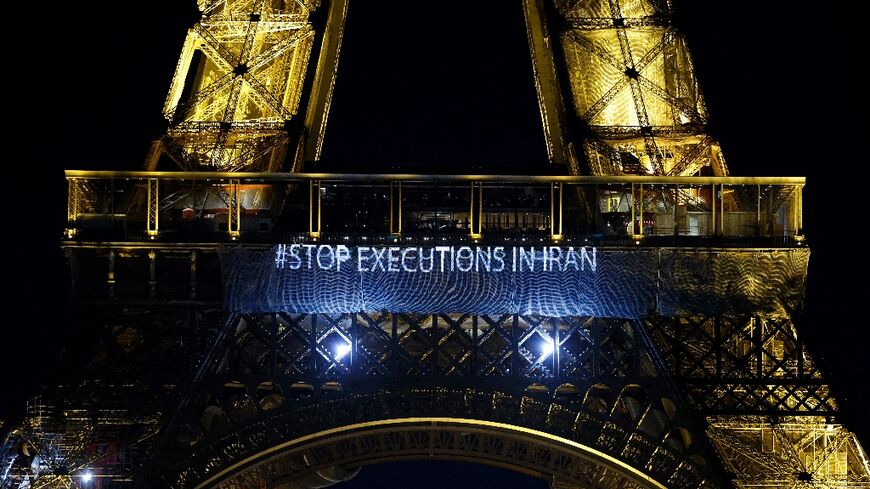

The alleged destruction has been condemned by the United States, which has also criticised the ongoing persecution of the Bahais, as have United Nations officials.

Unlike other minorities, Bahais do not have their faith recognised by Iran's constitution and have no reserved seats in parliament. They are unable to access the country's higher education and they suffer harassment ranging from raids against their businesses to confiscation of assets and arrest.

Even death does not bring an end to the persecution, the BIC says.

According to the community, following the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, the authorities confiscated two Bahai-owned burial sites and now forcibly bury their dead in Khavaran.

The cemetery is the site of a mass grave where political prisoners executed in 1988 are buried.

"They want to put pressure on the Bahai community in every way possible," Simin Fahandej, the BIC representative to the United Nations, told AFP.

"These people have faced persecution all their lives, were deprived of the right to go to university, and now their graves are levelled."

The US State Department's Office of International Religious Freedom said it condemned the "destruction" of the graves at the cemetery, adding that Bahais "in Iran continue to face violations of funeral and burial rights".

- 'Going after the dead' -

The razing of the graves comes at a time of intensified repression of the Bahai community in Iran, which representatives believe is still hundreds of thousands strong.

Senior community figures Mahvash Sabet, a 71-year-old poet, and Fariba Kamalabadi, 61, were both arrested in July 2022 and are serving 10-year jail sentences.

Both were previously jailed by the authorities in the last two decades.

"We have also seen the regime dramatically increase Bahai property seizures and use sham trials to subject Bahais to extended prison sentences," said the US State Department.

At least 70 Bahais are currently in detention or are serving prison sentences, while an additional 1,200 are facing court proceedings or have been sentenced to prison sentences, according to the United Nations.

The Bahai faith is a relatively young monotheistic religion with spiritual roots dating back to the early 19th century in Iran.

Members have repeatedly faced charges of being agents of Iran's arch-foe Israel, which activists say are without any foundation.

The Bahais have a spiritual centre in the Israeli port city of Haifa, but its history dates back to well before the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

"The fact that they are going after the dead shows that they are motivated by religious persecution and not by a perceived threat to national security or society," said Fahandej.

Repression of the Bahais, 200 of whom were executed in the aftermath of the Islamic revolution, has varied in strength over the last four-and-a-half decades but has been in one of its most intense phases in recent years, community members and observers say.

The UN special rapporteur on human rights in Iran, Javaid Rehman, told the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva this week he was "extremely distressed and shocked at the persistent persecution, arbitrary arrests and harassment of members of the Bahai community".

Fahandej said it was not clear what had prompted the current crackdown but noted it came as the authorities seek to stamp out dissent of all kinds in the wake of the nationwide protests that erupted in September 2022.

"The treatment of the Bahais is very much connected with the overall situation of human rights in the country," she said.