From carpark to 'world's largest underground hospital' in 30 hours

The level three basement carpark in northern Israel's Rambam hospital is usually what it is called -- a place for people to leave their vehicles.

But in 30 hours this week, staff transformed the cavernous space into a huge underground hospital, equipping it with 1,300 beds, complete with fittings for oxygen, medical and sanitary supplies.

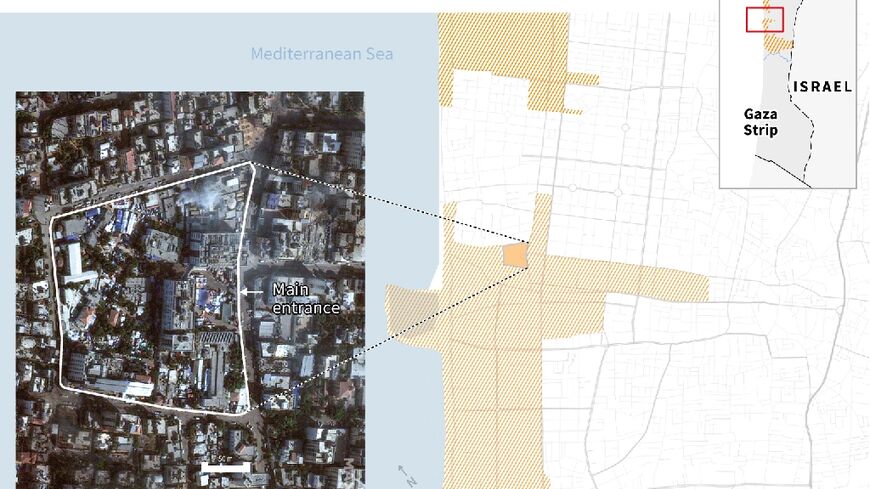

Israel is in the midst of a war to "crush" Hamas, after the Palestinian Islamists stormed its southern border at the weekend, shooting dead more than 1,200 people in the streets and in their homes.

Israel has since been pounding Hamas targets in the Gaza Strip, where 1,537 people have been killed.

Located in Haifa, about 50 kilometres (31 miles) from the border with Lebanon, Rambam hospital readied the underground facility as Israel has also traded cross-border fire with Hezbollah and allied Palestinian factions in Lebanon since Sunday.

It was in fact a 2006 war with Hezbollah which had prompted the hospital to come up with its dual-use idea.

At that time, 400 rockets rained down around the hospital, said anaesthetist Philippe Abecassis, 62.

Patients were then moved down to the cellar which was bare, with the ground still covered in sand.

The hospital, which had already began digging works for an underground carpark, then had "this idea, that if war were to return -- and unfortunately in the 75 years of Israel's existence, we know that war returns -- we could use this parking as an underground hospital," said Abecassis.

- 'Sanctuaries' -

Engineers and architects then worked to design a space in the basement where three levels of parking space could be easily switched into a treatment centre.

"The facility has three floors. Every floor is over 20,000 square metres. On regular days, it is a parking lot and in emergency, it becomes the biggest underground hospital in the world of 2,000 beds," said Michael Halberthal, director general of the Rambam hospital.

Sockets, pipes and other essential fittings are usually concealed.

But in times of crises, like this week, they quickly came into use as hospital staff brought in the beds and other medical equipment.

During AFP's visit on Thursday, basement three was already set up, with large fabric conduits pumping air conditioning into the large space.

Monitors are plugged in. Showers, sinks, toilets linked to water supplies, and sewage connections also fitted.

Cables between cubicles allow oxygen supplies to flow in, or for human secretions to be pumped out.

The 1,300 beds were in place, complete with clean sheets and blankets.

Works were ongoing in basement level two, where 700 beds will be installed.

And basement level one, where cars were still parked on Thursday, could be turned into a decontamination room and a triage area in case of a chemical attack.

Four operating theatres are planned underground, in addition to the 14 existing in the aboveground levels, where construction has been fortified in case of bombings.

"I never thought I'd see this time in my career. But well, there we are," Abecassis said, sighing.

For the doctor, even having to take such a measure to protect patients is "philosophically very difficult to understand" as "hospitals should be sanctuaries".

- 'Can't count on luck' -

But health establishments are not always spared.

On Wednesday, a rocket struck a hospital in southern Israel's Ashkelon city, without killing anyone.

"We can't count on luck," said Halberthal, director of Rambam hospital.

"We are waiting, depending on the development in the north. But if we will need to bring down the patients, within eight hours, all the patients will be over here.

"So all the patients, the staff, everything is totally protected. And we continue with regular medical activities."

The hospital also has food, petrol, oxygen and medical supplies enabling it to be self-sufficient for three days, said Halberthal, who hoped the underground hospital would not have to be used.

The hospital was already deployed during the coronavirus crisis, when staff learnt the difficulties of treating patients in a cavernous space without partition.

Noise insulation emerged as an issue, as that would have prevent others from hearing the cries of pain, said Abecassis.

Hospital staff have also sought to liven up the area by decorating the walls with posters of flowers, in the hopes of easing discomfort particularly for those with claustrophobia.

"This place may not be the prettiest, but it is the safest in the hospital," said Einat Perex, deputy chief of nurse.

As sirens wailed in the north of the country on Wednesday over suspicions of an "aerial infiltration" that was finally ruled out by Israel, about 100 patients were guided down to the area, before being led back up a few hours later to their rooms, said Israeli reservist Dan Kammoun.

"This place is unbelievable," said Perez, adding that "it is a hospital, not a carpark".