Iraq's climate migrants flee parched land for crowded cities

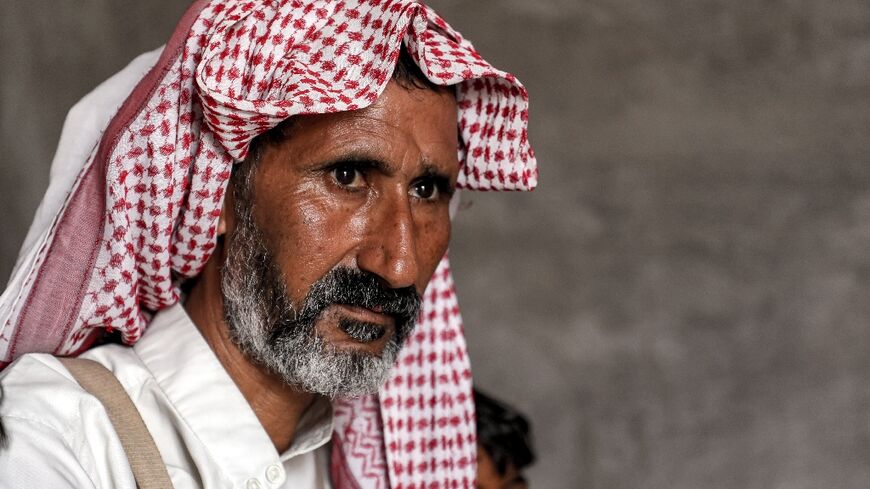

Haydar Mohamed once grew wheat and barley, but Iraq's relentless drought has forced him off the land and into the city where he now works in construction and drives a taxi.

"The transition is difficult," said Mohamed, 42, who abandoned village life several years ago for a shantytown in the central city of Karbala.

He is part of a growing wave of climate migrants in Iraq, a country that is on the frontlines of the global warming crisis.

Years of dire water scarcity left him no choice but to move, said the father of five.

"If you don't work," he said, "you don't eat."

Until 2017, Mohamed, like his father before him, worked farmland in the remote village of Al-Khenejar in Iraq's southern Diwaniya province.

In a good year, they would harvest 40 or 50 tonnes of grain, he said.

But "water shortages have impacted farmland and livestock", said the man with a neat moustache and a traditional black robe worn over a white gown.

"In our region, there is no work," he said. "I have children in school, which involves expenses. We needed a livelihood."

He now earns about $15 a day on construction sites in the holy Shiite city, which thrives thanks to a steady flow of religious pilgrims.

To supplement his income, he works shifts as a taxi driver.

Near his home, cows graze on rubbish strewn across the dusty ground and grey cinderblock buildings line the bumpy alleys, connected for free by the municipality to power lines and water pipes.

- Blistering heat, dust storms -

The United Nations ranks Iraq, still recovering from decades of dictatorship and war, as one of the world's five countries most impacted by some effects of climate change.

The economy is driven by oil exports, but the second biggest sector is agriculture, which makes up five percent of GDP and employs 20 percent of the workforce.

Water scarcity is extreme in the country of 42 million that endures blistering summer heat and regular dust storms, the shortfall worsened by upstream river dams in Turkey and Iran.

The UN says nearly one in five people live in an area hit by water shortages, while state authorities have been forced to limit areas designated for cultivation.

In central and southern Iraq, "12,212 families were still displaced due to drought conditions" in March, said the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Across Diwaniya province, 120 villages now rely on trucked water deliveries, up from 75 last summer, said the provincial governor Maitham al-Chahd.

"Thousands of hectares have been abandoned," he said.

Among the other worst hit provinces are Dhi Qar and Maysan, said the IOM, which estimates that 76 percent of displaced people move to cities.

The rural flight piles pressure on urban areas where infrastructure is dilapidated after decades of conflict, corruption and mismanagement.

A UN report last month warned of the risk of "social unrest" driven by climate factors.

"In the absence of sufficient public services and economic opportunity... climate-driven urbanisation and mobility can reinforce pre-existing structures of marginalisation and exclusion," it said.

- Deserted countryside -

Chahd said rural migrants faced unemployment in the cities, where there "are not enough job opportunities" for all the newcomers.

"Public services cannot meet the needs of growing city populations."

Meanwhile, rural areas are being deserted, including the village of Al-Bouzayad, where the main irrigation canal has completely dried up.

About 100 families have left in the past two years, and today only 170 households are still listed on the municipal register, said mayor Majed Raham, several of whose relatives have joined the exodus.

Abandoned adobe houses sit next to unfinished yellow-brick constructions. In one empty dwelling, rooms stripped of their doors and windows show signs of the lives that have been upended.

Portraits of the revered Shiite figure Imam Hussein still hang on the walls, a padlocked room contains personal items, and a satellite dish gathers dust in the courtyard.

Those who have stayed depend on insufficient water deliveries made by tankers sent by the governorate authorities, which they deplore.

Raham said most survive on either state benefits or money earned by their children, who commute daily to the nearest town.

"The majority want to leave," he said, "but they don't have the means."